History of Christmas in America

Throughout the course of the Middle Ages, Christmas was wholly supported by the Church and was thus celebrated festively around the world. It survived well through the Reformation and did not become a subject of controversy until the 17th century in England. At this point in history, the Christmas season had devolved into a time of excessive drinking and rioting which disturbed many Christians, particularly the Puritans. Of course, attitudes varied widely about how Christmas should be celebrated, and these conflicting views made their way to early American colonies. Though difficult times prevented indulgent celebrations for any of the initial settlers, some distinct differences arose between the early Northern and Southern colonies.

In the South, America’s first clearly recorded Christmas was at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 (if we exclude a celebration in 1604 by French settlers when they unsuccessfully tried to establish a colony on St. Croix Island off the coast of Maine).1 The Jamestown settlers departed from England on Dec. 19, 1606 and spent their first Christmas together on board their ship. Unfortunately, due to “unprosperous winds,” the ship was “kept six weeks in the sight of England.”2 Many of the men were sea sick, but they made the best cheer they could. Little did they know that their first Christmas in America would prove to be much more difficult.

Jamestown was founded on May 13, 1607, but by Christmas of that year, only about 40 of the original 100 settlers had survived. Captain John Smith, their leader, was absent. He had undertaken the dangerous mission of securing food from the Native Americans. Thus, the first official Christmas on American soil was a solemn one commemorated in a simple wooden chapel. Fortunately, after many trying years, conditions improved, and by 1624, Smith recorded:

“The extreme winde, rayne, frost and snow caused us to keep Christmas among the savages where we were never more merry, not fed on more plenty of good Oysters, Fish, Flesh, Wilde Fowl and good bread, nor never had better fires in England.”3

With time, as Jamestown and other newly established Southern colonies became prosperous, they developed a reputation for festive, hospitable and even lavishly decorated Christmas celebrations.

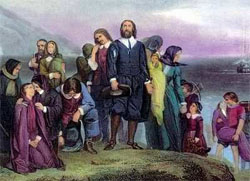

Compared to the South, New Englanders had quite a different view of Christmas. Many of these colonists had been appalled at the behavior (drunkenness, rioting, etc.) demonstrated during the Christmas season in their native England. From the time these Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock and set foot in the New World in 1620, it appears that Christmas was essentially ignored.

William Bradford, governor of the Plymouth Colony, recorded how he had called his citizens out to work on Christmas of 1621, as was his custom. Some men who had recently arrived to the colony told Bradford that it was “against their consciences” to work on Christmas day. The governor said he would “spare them till they were better informed,” but when he returned at noon, he found the men playing sports in the street. Here is what the governor recorded (he speaks in the third person as a historian):

“So he went to them and tooke away their implements, and tould them that was against his conscience [notice how he uses their own words against them!], that they should play and others worke. If they made the keeping of it matter of devotion, let them kepe their houses, but ther should be no gameing or revelling in the streets. Since which time nothing hath been attempted that way, at least openly.”4

Several years later, the “ban” on Christmas actually made it into the law books of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. For over 20 years (1659-1681), anyone caught celebrating Christmas was subject to fines. The law read as follows:

“For preventing disorders, arising in several places within this jurisdiction by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other communities, to the great dishonor of God and offense of others: it is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.”5

Even after the ban was lifted, animosity toward Christmas celebrations remained among colonists for many more years. Sadly, much of the bad behavior that early New Englanders tried to prevent showed up anyway. However, good traditions made their way to our young nation, as well. Immigrants from all over Europe were coming to America with long held Christmas traditions. In Germany, for example, Christmas had evolved into a time for family, giving and worship.

Americans began to embrace such traditions, and the American Christmas started to take shape. The early 19th century poem now known as “’Twas The Night Before Christmas” is credited with popularizing St. Nicholas and making children an important part of Christmas. Furthermore, in 1843, Charles Dickens published the classic story A Christmas Carol which helped to solidify the perception of Christmas as a time of giving and hope.

It is not surprising that the first three states to declare December 25 a legal holiday were Southern states: Louisiana (1831), Arkansas (1831) and Alabama (1836).6 Other states would follow and by 1870, Christmas was declared a U.S. Federal holiday. At present, American Christians have, for the most part, returned to the ancient Christian view as articulated by the respected theologian Augustine (354-430 AD): “So then, let us celebrate the birthday of the Lord with all due festive gatherings.”7 Surely it is good when Christians appropriately celebrate the birth of the one for whom they exist . . . Jesus Christ!

This page was created by:

Back to main Christmas History page.

We welcome your ideas! If you have suggestions on how to improve this page, please contact us.

Information on this page was drawn from our featured Christmas book.

You may freely use this content if you cite the source and/or link back to this page.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Hatch, Jane M. The American Book of Days. H.W. Wilson Company, 1978, p. 1145.

2 Barbour, Philip L., editor. The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580-1631), Volume I. University of North Carolina Press, 1986, p. 204.

3 Smith, John. Contributor: John Milliken Thompson. The Journals of Captain John Smith: A Jamestown Biography. National Geographic Society, 2007, p. 114.

4 Bradford, William. Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, 1606-1646. Edited by William T. Davis. Barnes & Noble Inc., 1908, pp. 126-127.

5 Massachusetts Bay Colony. From the records of the General Court, May 11, 1659. Retrieved August 6, 2008 from Massachusetts Travel Journal: http://masstraveljournal.com/features/1101chrisban.html.

6 Hatch, Jane M, p. 1146.

7 Witvliet, John D. and Vroege, David. Proclaiming the Christmas Gospel, Ancient Sermons and Hymns for Contemporary Christian Inspiration. Sermon by St. Augustine, Baker Books, 2004, p. 31.