Liberty Bell

Most people have grown up believing that immediately following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, news of freedom was proclaimed by the ringing of the Liberty Bell in the steeple of the Philadelphia State House. This legend has been traced back to a 1847 fictional story written by George Lippard for The Saturday Currier in which an elderly bellman waits in the State House steeple for word as to whether or not Congress will declare independence. As the old man begins to doubt Congress’ resolve, his grandson, who had been eavesdropping at the doors of the State House, yells, “Ring, Grandfather! Ring!” According to US History.org:

According to US History.org:

“This story so captured the imagination of people throughout the land that the Liberty Bell was forever associated with the Declaration of Independence. The truth is that the steeple was in bad condition and historians today highly doubt that the Bell actually rang in 1776. However, its association with the Declaration of Independence was fixed in the collective mythology” (www.ushistory.org).

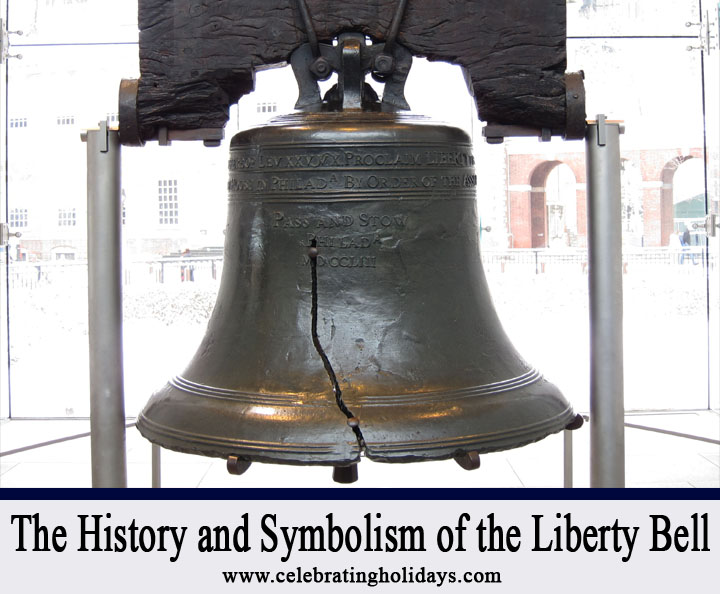

Furthermore, the first celebration of independence did not happen until July 8th, when the Declaration was first read aloud to the people of Philadelphia in Independence Square, or the State House Yard, as it was then called. John Adams recorded in a letter that “the bells rang all day and almost all night.” He made no specific mention of the State House bell, as it was then called. The name “Liberty Bell” was not even used until the 1830’s when the anti-slavery movement adopted it as a symbol of freedom. The bell was originally ordered by the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1751 to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of William Penn’s 1701 Charter of Privileges (Pennsylvania’s original Constitution). The Charter speaks of the rights and freedoms of common people. Penn’s ideas on religious freedom, Native American rights, and the inclusion of citizens in enacting laws were quite unique for his time. The inscription on the bell reads:PROCLAIM LIBERTY THROUGHOUT ALL THE LAND UNTO ALL THE INHABITANTS THEREOF LEV. XXV. V X. BY ORDER OF THE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF PENSYLVANIA FOR THE STATE HOUSE IN PHILADA PASS AND STOW PHILADA MDCCLIII

The verse is from Leviticus 25:10 and begins with the words, “Consecrate the fiftieth year.” It seemed particularly well suited to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Penn’s Charter, and to honor the man who believed so wholly in liberty for all people. Unfortunately after arriving in America, the bell cracked when it was being tested. The bell had to be melted down and recast twice before it rang successfully (at which point it was used regularly to summon leaders for meetings and to call citizens together for special announcements and events). Among the more significant historical occasions, “it tolled when Benjamin Franklin was sent to England to address Colonial grievances, it tolled when King George III ascended to the throne in 1761, and it tolled to call together the people of Philadelphia to discuss the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765 [Acts that would contribute to starting the Revolutionary War, see our July 4th History page] (www.ushistory.org). The bell apparently tolled quite frequently, because a petition was sent to the Assembly in 1772 complaining that the people in the vicinity of the State House were “incommoded and distressed” by the constant “ringing of the great Bell in the steeple.” In September 1777, the bell was hastily removed from the State House (along with all the other bells in Philadelphia) and hidden in the floorboards of a church in Allentown. The British army was approaching and people were afraid that they would melt down the bells for ammunition. The bell was returned to Philadelphia after the British left the city in June of 1778. Several years later, when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital (1790-1800), records indicate that the Bell was used to call the state legislature into session, to summon voters to submit their ballots at the State House window, to commemorate Washington’s birthday and, of course, to celebrate the Fourth of July. It is difficult to tell what kind of symbolic significance the bell had for early Americans. In 1816, the bell was almost destroyed when the Pennsylvania Legislature ordered the destruction of the State House. Fortunately, the city of Philadelphia agreed to pay $70,000 for the property and thus preserved it. Yet, interestingly, in this transaction, the Liberty Bell was not listed as a significant fixture of the State House (Myers, Robert J., Celebrations, Doubleday and Company, 1972, p. 196). The bell continued to ring at various events, but on July 8th, 1835 (exactly 59 years after the first celebration of Independence), it developed a serious crack while tolling at the funeral of Chief Justice John Marshall. It rang for the last time on Washington’s birthday in 1846. After that, the crack was so deep that the bell had to be put to rest. Today, the Bell resides at the Liberty Bell Center in Philadelphia (which opened in October 2003). On every Fourth of July, descendants of the signers of the Declaration, gently tap the bell 13 times to honor the patriots from the 13 original states. This page was created by: Back to main July 4th Symbols page.

We welcome your ideas! If you have suggestions on how to improve this page, please contact us.

You may freely use this content if you cite the source and/or link back to this page.

Back to main July 4th Symbols page.

We welcome your ideas! If you have suggestions on how to improve this page, please contact us.

You may freely use this content if you cite the source and/or link back to this page.